(Well last week actually.)

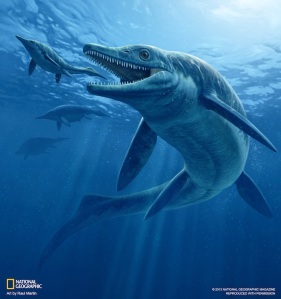

Thalattoarchon saurophagis looking big mean and ichthyosaurian. Here it’s chasing a smaller mixosaur (e.g. Phalarodon) which has been found nearby. Artwork by Raul Martin.

You’re in for a BIG surprise! We may only be in the third week of 2013, but already there’s some exciting news on the ichthyosaur horizons. Last Monday (7 January 2013) came the exciting news of a new macro predator; because adding ‘big’ to the front of ‘predator’ just makes it more awesome.

So what have we got here. The name pretty much says it all: Thalattoarchon saurophagis, the ‘reptile eating ocean ruler’ (Fröbisch et al. 2013), it doesn’t run off the tongue, but a little skip isn’t too bad.What we have here is a big and mean beast that could probably have eating most of the animals around it. There are several reasons why this find is odd and important: first, how is different to other ichthyosaurs?

Om nom nom

Thalattoarchon is a big ichthyosaur, estimated to be at least 8.6 m. This is a similar size to the Late Triassic Cymbospondylus and as big as the largest Temnodontosaurus from the Early Jurassic. (It does pale in comparison to the largest Shastasaurus [~22 m], but they’re likely in completely different ecologies.) Thalattoarchon has a skull that is around twice the size of a similarly sized Cymbospondylus, and the skull is the real business end.

In the mouth you find many teeth. With Jurassic ichthyosaurs, I’m used to dealing with teeth that are a few centimetres long, about one centimetre across and very smooth all over. Thalattoarchon had big teeth, more than 12 cm for the largest, and these weren’t smooth; they were equipped (in life) with a pair of sharp slicing edges. This condition is called bicarinate, literally ‘two-keeled’. It’s found in a few groups, such as in the crocodilian Rimasuchus, and the mosasaur Hainosaurus, but infrequent in ichthyosaurs. Some examples of Temnodontosaurus platyodon have them as does the enigmatic Himalayasaurus tibetensis. The shape of the teeth puts it in the ‘cut’ group of Massare (1987).

Macro, sch-macro…

So what’s so special about this beast, other than it’s a large, predatory ichthyosaur with big cutting teeth? Really, you need more than that?

Besides being a macropredator, Thalattoarchon saurophagis has the distinction of being one of, if not the, earliest macropredatory tetrapods in the oceans. Tetrapods are vertebrates that have four limbs, a group made up of amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, plus a few others. This notably excludes the fish, which don’t have limbs, but have many fins instead.

Nowadays, there are two animals that hold the top rung in the oceanic food chain, the Orca or Killer Whale (tetrapod) and Great White Shark (fish). In the Cretaceous there were the mosasaur Tylosaurus (tetrapod) and the ‘bulldog’ fish Xiphactinus. Xiphactinus has been made famous by the ‘fish in a fish’ fossil: a Xiphactinus was killed eating a fish that was too big. The Jurassic had the pliosaurs Pliosaurus and Liopleurodon (both tetrapods), which wasn’t the 25 m in length that Walking with Dinosaurs suggested, although others may have come close. And the Triassic had Thalattoarchon. But what about before then?

Despite there being about 300 million years before Thalattoarchon, and there being tetrapods for ~100 Ma of that, the main threat in the oceans then were big fishes. The meanest looking was Dunkleosteus, not just because it was up to 10 m long, but also it’s head was covered in thick bony plates, and its mouth full of slicing bony plates too. The Devonian (419–358 Ma) is famous for its placoderms, to which Dunkleosteus belongs, the armoured fishes that specialised in bony defence across their bodies.

All change at the top

The appearance of Thalattoarchon saurophagis marks a change from the fish-tipped Palaeozoic food webs to the Mesozoic and Cenozoic (including today) tetrapod-dominated oceans. The end of the Permian (252 Ma) was marked by the largest mass extinction known; a frequently quoted figure is 95% of life in the oceans died out. Thalattoarchon is from rocks deposited at least 244 Ma, within 8 Ma of the Permian–Triassic boundary, and only 4 Ma from the earliest known ichthyosaurs (Thaisaurus and Utatsusaurus; Shikama, Kamei and Murata 1978; Mazin et al. 1991; Nicholls and Brinkman 1993). This is a very rapid diversification to occupy these vacant niches. The Triassic in general was an exciting for all marine animals to spread and colonise new areas, the weirdness of early sauropterygians is a good example.

References

MAZIN, J.-M., SUTEETHORN, V., BUFFETAUT, E., JAEGER, J.-J. and ELMCKE-INGAVAT, R. 1991. Preliminary description of Thaisaurus chonglakmanii n. g., n. sp., a new ichthyopterygian (Reptilia) from the Early Triassic of Thailand. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences. Série 2, Mécanique, Physique, Chimie, Sciences de l’univers, Sciences de la Terre, 313, 1207–1212.

SHIKAMA, T., KAMEI, T. and MURATA, M. 1978. Early Triassic Ichthyosaurus, Utatsusaurus hataii gen. et sp. nov., from the Kitakami Massif, Northeast Japan. Science Reports of Tohoku Univeristy, Second Series (Geology), 48, 77–97.